1437 Active Guests

|

Get notified when this page is changed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1437 Active Guests |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Native American 4-H HistoryWhile little is mentioned on 4-H programming with Native American audiences in the Franklin Reck 4-H History of 1951, the history book "4-H: An American Idea 1900-1980" by Thomas Wessel and Marilyn Wessel devotes approximately two pages (p. 185-187) to the subject. This is shown below in its entirety. "Up into the decade of the 1960s there is little documentation of 4-H work with the Native American youth stemming from the national level... that is, until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Act was not limited to equality for Blacks - it prohibited discrimination against any class of people. Such a universal application, while placing emphasis on the South, forced Northern Extension workers to realize that they, too, had to get their house in order rapidly. "Native Americans presented a special case. They were after all legally segregated through a system of reservations stretching across the nation. In many instances, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had duplicated services available to other Americans through its offices. Extension was no different. The BIA established an Extension division to serve the needs of the reservation in 1928. A. C. Cooley, former director of Extension in New Mexico, served as the first head of the Indian Extension Service. Because agriculture had been a major part of the government's program for Indian assimilation since the latter part of the nineteenth century, reservation agents hired "expert farmers" to teach skills and cropping methods to adult Indians and conduct classes for Indian children on the reservations and at off-reservation boarding schools. Most expert farmers used bulletins and other literature produced by Extension and the experiment stations. In later years, the BIA sent its Indian Extension agents to training schools and other special programs offered by state Extension services. To the extent that the Indian Extension agents were assigned to conduct or wanted to do 4-H work, reservation children received a program similar to their White counterparts. The system of separate Extension services in the BIA lasted until 1956 in most areas. After that time, reservations contracted with land-grant universities to provide agents skilled in agriculture, home economics and youth work. By the late 1960s, when many tribal councils were striving to gain a measure of autonomy from federal government control, they opted to diminish or terminate their contracts with Extension. In many cases, the tribes preferred to hire their own educators, but 4-H and Extension methods, materials and training sessions were often used. "In the early years of Indian 4-H work, the programs for White children were merely adapted to the reservations. Skills in clothing, food production, grain and animal production, demonstrations and fair were often a part of reservation life. Sarah Harmon, a retired Arizona Extension leader, remembered an early visit to the Hopi Reservation where she found the Extension agent working on a 4-H electric project as a way to prepare youngsters for a major change in their lives. "A 4-H group from Coconino County, Arizona, made the news in 1971 when members helicoptered a dozen rabbits into the Havasaupai Indian Reservation with the hope of beginning a 4-H rabbit project for the people who lived in the village of Supai deep in the Grand Canyon. There were many other such examples of 4-H groups working with reservation children. But, by the 1970s, it was very difficult to make any generalizations about 4-H programs on American Indian reservations. Some tribal educators raised serious questions about the adaptability of 4-H programs, literature and contests to the Indian culture. Adele King, a Navajo home economist, found most 4-H materials unsuited to her reservation's youth so she either made her own or borrowed from Indian Youth Programs in Canada. She also worked to lessen 4-H competition in her youth education efforts because she questioned its effect on her people. Whenever possible. King preferred to see youngsters involved in nontraditional 4-H projects more closely related to tribal culture. She did agree, however, that the learning by doing 4-H method transferred well. "Only a few hundred miles away, Verneda Bayless, another Extension worker, used the most traditional 4-H methods to teach public speaking to Indian children living in the Southern Pueblo villages surrounding Albuquerque. In San Felippe, Pueblo children attending the Indian summer school did poems, stories and extemporaneous speeches under Bayless' direction. She scored the youthful orators, urged them to slow down and use gestures, and gave the shyest child a hug when the words would not come. One Indian 4-H'er, Margaret Salazar from the Islete Pueblo, won a trip to National 4-H Congress with her public speaking skills. In contrast to the Navajo experiences, Bayless viewed competition as an important element in Indian 4-H programs. "In an attempt to design a workable 4-H program for American Indians, Extension sponsored the Northwest Indian 4-H Youth Seminar on the Warm Springs Reservation near Portland, Oregon, in 1977. With King and Bayless among the participants, the seminar progressed into an idea exchange. If a single theme emerged from the three-day conference, it was that while a culturally ignorant Extension agent certainly could make mistakes there was no ultimate "right way" to do Indian 4-H work. The richness and diversity of the Indian people would not allow for a prescriptive program any more than all the children of Chicago could be expected to take a single 4-H project. "The advent of 4-H Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) did provide for some additional service to Indian children, but their numbers are still small in comparison to most other minority participants. Statistics on Indian participation in 4-H became available in 1972 when affirmative action guidelines required that members of various minority groups be counted. 4-H was reaching 25,881 American Indians in 4-H clubs or special interest groups by 1975. While that did not include youngsters reached by television or 4-H EFNEP programs, it represented less than 1 percent of the total population for that year." While there is little record of early 4-H and Native American history initiating from the national level, a number of states containing reservations worked with the tribal counsels in a variety of ways. And, interestingly, the national volunteer magazines "National 4-H News," carried numerous news stories and features about Native Americans over the years, starting in 1943 and running up through the early 1970's. Here are some of the National 4-H News stories... they may not be heavy into the traditional aspects of "history" as we know it, but they provide a variety of first hand reports on targeted activities and club participants which gives us a glimpse of 4-H clubs on reservations 50, 60 and 70 years ago. They are good stories... success stories, and therefore should be included as part of our history documentation on 4-H and Native Americans. Arizona"Indian 4-H Members Do Well With Purebreds"National 4-H News April 1952, page 28+"Great Leader of the 4-H Livestock Club" is the meaning of an Indian name given County Agent Sam W. Armstrong in Gila county, Arizona. And Sam is proud of the San Carlos Indian 4-H livestock club that brought about his renaming. The club was organized in 1949 with two girls and 18 boys taking livestock projects. In 1950, 8 girl and 20 boys enrolled. This year, the club really expanded, with 13 girls and 26 boys. All members completed projects each of the three years. In 1951, all of the Indian boys and girls had registered heifer calves as their projects. The two non-Indian members of the club had registered Hereford bulls.

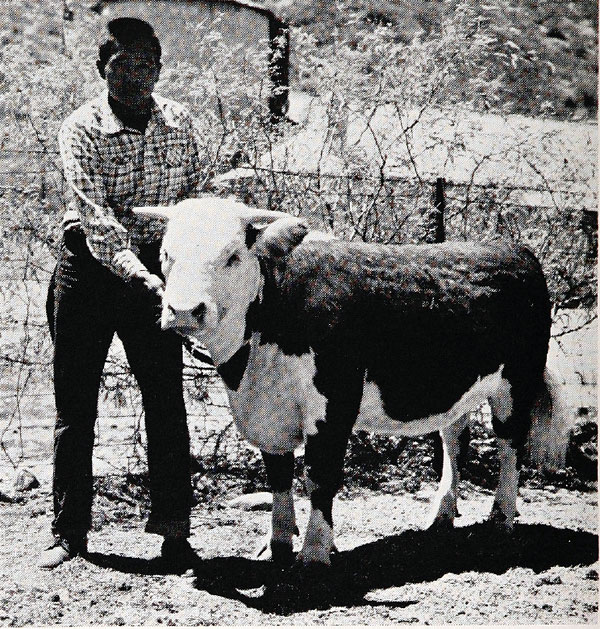

Ray Stevens, Jr., showmanship winner, with the heifer calf he raised as his 1951 4-H project on the San Carlos Indian Reservation in Arizona. (National 4-H News, April 1952) After a spring achievement day, the 1951 bulls and heifers were sold at auction at a regular Indian sale at the San Carlos reservation. Paul Buss' bull brought $420, with Hugh Veech's going for $340. The top four heifers sold for $290 each. They belonged to Ray Stevens, Jr., Dennis Nelson, Jr., Andy Polk, and Buck Kitcheyan. The lowest price for any of the heifers was $230. Orien Dillon, junior leader, was a very outstanding club boy this year. He fed a heifer and a steer and had nine boys and girls under his leadership. He went to Tucson as an alternate livestock judge for the State 4-H Roundup. Tommy Faras, Jr., another junior leader, is one of the best cattle feeders in the club. He is a sophomore at the Globe High School. He made the varsity football team the first year he tried out, and has the earmarks of being a star halfback before he graduates. He also plans to go to college. Tommy was a livestock judging team member at the 1950 Roundup. At a showmanship contest, Ray Stevens, Jr., won first with an outstanding heifer. He has completed three years of club work with livestock as his projects. He was junior leader this year and president of the club. He took third in beef cattle showmanship in 1950 at the Tucson Roundup. He won first in showmanship at San Carlos, competed in the beef cattle showmanship contest at Tucson in 1951, and has his call to go into the Army. Mygretta Russell, another junior leader, was one of two original girls in the club. She has completed three years of club work, and was on the livestock judging team that went to Roundup last year. "Another "H"... HOPI!"National 4-H News August 1959, page 11Your curiosity mushrooms into awe as you race along the desolate but majestic highland of strange, rugged beauty into the heart of the Hopi Indian nation in northern Arizona. You think: "How can these youths, many of them reared in traditional ways of clan life and an atmosphere of secret societies performing dances with snakes in their mouths as prayers for rain, adjust to modern American 4-H Club work?" You soon find out. Your Indian Service guide roars along a landscape of towering rock mesas and you rest your eyes upon an ocean of vast space and loneliness and watch the blowing sands that cover part of the highway. You've crossed the Navajo Reservation north of Holbrook and headed for Polacca where 161 Hopi boys and 212 Hopi girls are staging a 2-day 4-H Achievement Day. Here at Polacca Hopi youths have gathered from seven villages. Hopi girls, 11 to 17, are clustered around tables in a modern elementary school cafeteria. Their eyes dart intently as the judges comment on nearly 500 different items they have submitted in 4-H competition. On hand are aprons, sewing kits made out of cigar boxes covered with cloth, drawstring purses, blouses, skirts, dresses, wrist pincushions, biscuits, brownies, or cookies. Judges are from the University of Arizona Agricultural Extension Service and the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. With each judge is a local Hopi Indian 4-H leader who keeps records. "These certainly are above average clothing exhibits–very high quality," comments Miss Helen Church, clothing specialist for the University of Arizona Agricultural Extension Service. She awards blue ribbons to more than one-third of the clothing exhibits. The Hopi boys, most of them dressed in American blue jeans, straw-type cowboy hats, T-shirts, or sport shirts, scrub down their cattle. There are Hereford heifers, lambs, rabbits, chickens, a pig, and a few horses. Busy in the ring helping the boys is Hanson Tootsie, a Hopi 4-H club leader in charge of livestock at the show. So successful has he been in 4-H Club work, he is also vice-president of the 4-H Leaders Council of Navajo Country. The boys have been sufficiently successful in 4-H Club work in the past to win many prizes at the county fairs and win berths for State 4-H Roundup at Tucson. A few of the Hopi boys are busy drafting signs to be used with their individual or group demonstrations. Cable and posts are erected to give a cattle parasite-control demonstration. Some villages of Hopi land, such as around Hotevilla, have tended to cling to the more traditional ways of clan life. Yet, 4-H Club work has been successfully adapted to this different way of life, probably because of the Hopis being a family-oriented culture, just as 4-H Club work is family-oriented. "The Hopis are making great strides in their 4-H work," agree Amos Underwood, U of A county agent in Navajo county who handles the countywide 4-H program, and Jack Moore and Miss Clytail Ross, both of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, who work with local Hopi 4-H leaders in the program. "The Hopi's are using 4-H programs to tie the community closer together through adults and children." "4-H Goes Functional for Indians"National 4-H News June, 1972, page 20+Tucked between Grand Canyon National Park and Grand Canyon National Monument in Coconino County, Arizona, lies Havasupai Indian Reservation, 518 lush acres surrounded by 2,400 feet of sheer canyon walls. Until recently, when helicopter charters became available, the only way to reach the village of Supai and its 250 inhabitants was by horse or mule. Or, on foot! Either way, it wasn't easy. Hilltop, a small community at the end of a lonesome 70-mile gravel road is as close as you can get by car. Beyond that is a twisty eight-mile trail that winds into the canyon. But such inaccessibility didn't stop 4-H from penetrating. Determined teen 4-H'ers from relatively nearby communities one day boarded a helicopter armed with a cage full of rabbits they'd lashed to an outside cargo rack, and flew into the canyon. Why rabbits? The Bureau of Indian Affairs, who co-sponsored with University of Arizona, a two-week 4-H experience during which 4-H teens helped Indian youngsters set up projects, felt the Indians' diets lacked protein. How better to augment them than to start a rabbit project among the youth? Shortly after occupying cages feverishly built to protect them from dogs, does commenced having bunnies and the program was on its way. Meanwhile, because many Indian families earn their livings packing tourists in and out of the canyon, a 4-H horse project was a natural. So the enterprising 4-H teens decided to start one with a gymkhana–a horse games event–at the reservation's rodeo grounds. Time for the well-publicized event came and went. No Indians. Teens thought they'd failed. But by the time they had four poles set in the arena for a pole-bending race, a crowd had materialized. Gymkhanas and daily swims in a 50-foot pool on Havasu Creek were recreational highlights of the two weeks, during which Indian youngsters completed leathercraft, rope craft and nutrition projects. But perhaps even more important, Arizona 4-H officials realized 4-H junior leaders make excellent instructors. "Our kids really related to the Indian youngsters–probably better than adults ever could," asserts state 4-H Specialist, Paul Drake. Teens like their experience, too. Says one: "It's quite rewarding to see even a few children respond to your work or your friendship. The Indian kids sometimes tried to ignore us, but you could catch them looking or smiling at you." Idaho"In Any Language - They're Builders.National 4-H News May, 1960, page 19Fort Hall 4-H Klatiwah Club is a name with a pleasant rhythm, but it's more than that; it's the name of a young Idaho club which got off to a fast start on service to its community. Saying "4-H Klatiwah Club" in the Shoshone Indian language is about the same as saying "4-H Builders Club" in English. This Klatiwah Club was organized in December 1959 on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho. Four older boys–Bernard Eschief, Gilbert Teton, Carl and Lewis Olney–were the first members of the club. By the time of its second meeting, the club had seven members, with the addition of Bernadine Eschief, Belma Truchot and Irene Olney. Both of the projects that the group agreed on at once were for community service. First, they would see that some needy family had a good Christmas. Second, they would hold a party for students home from school for Christmas vacation. The 4-H'ers collected food, packed a basket, and went as a group to deliver it. There were some gifts for the family, too. The potluck dinner and party for students was held in the Fort Hall tribal building. Soft blue lights enhanced the decorations inside the building. Mixers such as the balloon dance, passing the orange and others were used. Thirty local and home-from-school students enjoyed the party, which concluded with social dancing. In February, the Klatiwah Club was called on by the agricultural Extension service to take part in a television program–one of a weekly series. They were asked to demonstrate parliamentary procedure as a useful guide for other clubs. The demonstration planned by the Klatiwah club included the 4-H pledge, given in the Shoshone tongue. There is talk now of a Fort Hall Fair, organized and operated by this club, which has some time to go before reaching its first anniversary. No matter how you spell it, these 4-H'ers intend to build a program for service to their community and to themselves. New York"Indian 4-H Club Relives Tribe's Past in Dramatic Pageant"National 4-H News October 1949, page 29+Full page photo feature. The beat of Indian tom-toms and the shuffle of dancing Indian feet have echoed once again far above Cayuga's waters. Heeding the advice of Mary Eva Duthie, Cornell University 4-H dramatic specialist, to "Look around you–every community offers ample material for original dramatics work," Edison Mt. Pleasant, a former member of the Tuscarora 4-H Club, wrote the pageant "Into the Setting Sun." He gathered his material from elderly Tuscarora chieftains who remember the history and culture of their forefathers. Wide-eyed 4-H Club boys and girls, at Cornell University for the annual N.Y. State 4-H Club Congress, watched enthralled while members of the Tuscarora club portrayed their romantic past. Residents of the Tuscarora reservation applauded it, too, because it pictures in tangible form a record of their history, and it has given their children a feeling for the fine traditions of their race. "Twenty-one teenage boys and girls are in the cast, all at least half-blooded Indians. With dignity and pride they wear the handsome beaded costumes and feathered headdresses once worn by their ancestors; revert to the rhythmic pace and sway of ancient ceremonial dances; speak in the stern, stone-faced accents of their forebears. The pageant opens with a council scene where the chief urges that the tribe move, since, through intermarriage, they are being absorbed by the Oneida Indians. Acceptance of the proposal is sad news for a young Tuscarora brave and his Oneida sweetheart. But their difficulties are solved by the Medicine Man who suggests that the maiden be adopted by the Tuscaroras. An adoption rite follows, and the ceremony of marriage with its ancient rites and dances. The final scene finds the tribe happily settled near the "Great Roaring Water," or Niagara Falls, where food is plentiful and the forest is safe. In gratitude the tribe assembles to sing a chant of Thanksgiving. The pageant and its actors indicate that the Tuscaroras are no "vanishing Americans"–but Americans who have combined their age-old culture and that of the white man with outstanding results. Tuscarora fruit and dairy farmers today are among the most prosperous in the State. Their children belong to one of the most active 4-H Clubs with enviable records in homemaking and gardening. Many of the young people go through high school and college. Noah Henry, a Tuscarora chief, and Mrs. Henry, who lead the club, tell of many members who have gone to State Club Congress and have taken awards in singing and play contests during their 12 years of leadership. Today the Tuscarora young people are doing the same things their neighbors do–and frequently doing better.

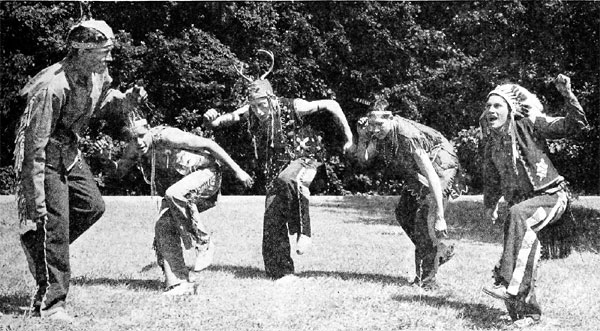

Leaders of the Tuscarora tribe perform the marriage dance, From left: David Roy, the Sachem Chief; Sanford Pembleton, a young brave; Kenneth Patterson, Ga-hoose, the Medicine Man; Donald Patterson, a brave; and Curtis Williams, Chief Constogas. (National 4-H News, October 1949) North Carolina; Nebraska"4-H Work Thrives for the Cherokees, Winnebagos, Omahas"National 4-H News June 1951, page 38Just southeast of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park in North Carolina is the 62,000-acre Qualla Boundary, home of the descendants of those Cherokee Indian tribes which were able to return to this region after their long trek westward in 1838. The term "boundary" is used in the same sense as "tract," or "reservation." During the years 1842-61 this acreage was purchased as a home for these Indians by William H. Thomas, an adopted son. The village of Cherokee is the capital of this Eastern Band of the tribe, and the school is maintained by the U.S. Government, with farming and homemaking as important parts of the curriculum. According to John Conyngton, Swain county agent, 4-H Clubs were successfully launched last year in the Big Cove, Birdtown and Cherokee schools in Swain county, and the Soco school in Jackson county. Organization work was done by Extension personnel in those counties, with local leaders from the Indian school cooperating. Conyngton reports that the boys and girls enthusiastically prepared exhibits for the Cherokee Indian Fair, and their efforts paid off, too, for each club was awarded a premium as follows: Big Cove, $25; Soco, $20; Birdtown, $15; and Cherokee, $10. At one of the Birdtown meetings Pansy Deal, county home agent, gave a home beautification demonstration. At the next meeting Mrs. Jesse Snegocki, club sponsor, asked that each member answer roll call by telling how this lesson had been applied at home. Everyone had done something, even though it was just removing an unsightly object from the front of the home. They had painted, planted shrubs, built walks, and so on. In the Bib Cove club, led by Ralph Hatclift, outstanding work has been done on individual projects and on crops such as strawberries, which were handled on a cooperative basis. Camping holds first interest with Soco members under the leadership of Kelly Underwood aided by Mrs. Don Craig, homemaking teacher. The Cherokee club is the youngest of th foursome, having just completed its organization with Mrs. Nan Tiner as sponsor. All have been greatly aided in their activities by Sam Hyatt, who has charge of the farm program at Cherokee. The boys and girls are much interested in raising better pigs, gardens and corn. They are active in wild life and forestry, too, and the girls are doing work on clothing, food preparation and room improvement. Conyngton says the 4-H club activities are already having an overall impact on improving farm and home conditions in the entire boundary. In Nebraska, the Winnebagos and Omahas have gone 4-H. Sixty Indian boys and girls attending the St. Augustine's Indian Mission, Winnebago, Nebraska organized a club. Although this is the only all-Indian 4-H "tribe" in the State, it has rough going at the money-poor mission school. Father Frank Hulsman, priest in charge of the mission, leads the boys' work and Sister Mary deLourdes, school principal, helps the girls with their projects. The boys will carry purebred Duroc swine as their project, while the girls will take homemaking and cooking. Oklahoma"Their Fightin'est Indian 4-H Club Called the Most Patriotic Outfit in Oklahoma"National 4-H News June 1943, page 9

Full page photo feature. According to county agent L. I. Bennett, they're the hardest fighting group of warriors in the country. All members of the Indian Riverside 4-H Club - the largest all-Indian 4-H Club in the state - with their 4-H club projects, they're helping Uncle Sam furnish food to the boys on the firing lines. They have a keen interest is seeing that food gets to the front because 18 Club members of their fellow tribesmen have joined the Army, Navy or Marines since Pearl Harbor. "You'll never find a more patriotic group of young people than these 4-H Club Indians," contends Bennett. As the older boys join the armed forces their projects have been taken over by younger members of the club and carried to completion. The girls can foods produced in the club's Victory Gardens. In addition to growing food, members of the Riverside Club are just as active in other 4-H project areas. At the State Round-Up Andrew Pahmahmie placed in the blue ribbon class in the State 4-H Style Dress Revue contest. Bernice Paddlety and Alva Mae Tapedo won a gold medal with their dairy demonstration at the State contest, Ruth Sardongei and Alva Walker won trips to the American Royal at Kansas City for placing first with their paint demonstration, and Luke Tainpeah and Tom Kauley were blue ribbon winners in the poultry demonstration contest. At the Caddo County Fair 53 of the club's girls made exhibits, winning a total of 82 ribbons. Dancing is also a major activity with these 4-H'ers. In fact, they earn most of the funds for their club by staging Indian dances and appearing on programs all over the State.

Riverside Indian 4-H Club members rehearsing for one of their dance numbers. L. to R. Beatrice Tahmalikera, Billie Tonpahhote, Lucy White Horse, Lee Monett Tsatoke, Myrtle Ann Beaver and David Joinkeen. (National 4-H News June 1943) "Thanks for America" was the main theme of their Achievement Week last December to climax the year's work. Instead of holding an achievement banquet as many clubs stage at the end of the year, this Indian Club celebrated their 1943 achievements in typical Indian style by setting aside an entire week for their achievement program. Each of the five daily programs staged were centered around one of the "H's" in the club emblem, and one for home. One day the training of the head was stressed, another day, the heart, then the hands, health, and then the home. Oregon"Indian 4-H'ers Tame The Range"National 4-H News October 1963, page 13+"A fine spring vacation, working all the time – but try to keep them away," laughed Extension Agent George Schneiter, who also directs boys' 4-H work at Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Central Oregon. The work was corral building and repairing fences around 31 acres of alfalfa and crested wheat which Rockin' 4-H Range Club had leased for early spring pasture. Nearly all of the 32 club members spent two or three of their vacation days on the fence project. This was the latest step in a continual-cycle program of livestock production and range management which has guided boys' 4-H work on the reservation since 1959. That year Joe Warner, who was Bureau of Indian Affairs range management specialist at Warm Springs, became Schneiter's first volunteer 4-H club leader and organized the Rockin' Range Club, with 10 boys enrolled. He developed a four-year program around study of range plants and ecology, range management, hay production and irrigation, livestock breeding, care and improvement. Charter Rockin' Rangers have completed the cycle once, with new members each year keeping the program going like a "round." Most of them also belong to allied clubs in forestry and tractor maintenance, led by Bob Short, BIA forester, and Darrell Thompson, school maintenance foreman. When Warner was transferred to Arizona, BIA Conservationist Dick Shaw assumed club leadership. In their club's first year, Rangers collected samples of important grasses and other plants and studied them. These were displayed at two county fairs, at livestock operators' meetings throughout the reservation, in Warm Springs store windows during 4-H Club Week, and in the agency Extension office. Chief study topics in 1960 were forage values of various plants and nature fits them to range. Warner and Schneiter helped the club lease five acres of idle farm land from a tribal member, beginning a range-livestock operation to be run eventually by the Rangers. 4-H'ers cut juniper posts and fenced the field. With borrowed equipment they planted alfalfa and grass. Previous instruction from a BIA soil scientist helped them determine fertilizer needs. Warner taught them something about making irrigation ditches and about siphon irrigation. A duty schedule spread the chores evenly.

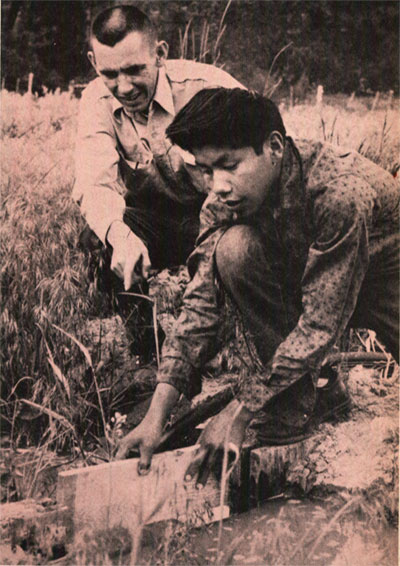

Joe Warner instructs a Rockin' 4-H Ranger on how to build a weir, or

irrigation dam. In the fall they pooled knowledge and experience to win second place team honors in the 4-H division of the state soil judging contest sponsored by the Soil Conservation Service. In 1961 the Rangers cut 21 tons of good alfalfa hay, hauled it to their winter feedlot and built a covering shed. They fenced the lot and built feeders and a maternity and sick bay for cows. By November they had assembled nine cows, mostly from home herds. Warm Springs tribal council made 1,000 acres of grazing land available in 1962. The young Rangers added some division fences and a small corral. That summer they helped build a stock water pond (stocked with fish, too,) on the land. In 1962 the club had 12 cows and 14 calves grazing on the summer range. Ted Ball, breeder of registered Herefords at Wamie, Oregon, has loaned an excellent herd sire – Beau Donald 300 – to the Rangers for short periods. Upon returning him to the owner, the boys trim the animal's hooves and groom him carefully. The Rockin' 4-H Range Club members also learned to do branding, vaccinating, castrating, weighing and recording of grain and other modern livestock practices in 1962. Some members sold steers, banking the money to build the herd later or to use for school. Members with heifer calves kept them for herd increase. Last spring the 4-H'ers negotiated with the owner of the 31 acres for early pasture, bargaining with money and an offer to repair the fence. Despite a slim treasury they reached agreement. Some of the boys live in the reservation dormitory, others with their families on reservation ranches. They range from fourth graders up to high schoolers. Not all may remain at Warm Springs to raise cattle and tend the range and forests, but for those who do there is opportunity, Schneiter feels, if they know how to protect and perpetuate their resources. 4-H and Native American History in AlaskaThe History of 4-H Club Work in Alaska began on July 1, 1930. The History of 4-H Club Work in Alaska 1930-1948 is available in the books and printed materials archives on the 4-H History Preservation website at: http://4-HHistoryPreservation.com/eMedia/epamphlets/Alaska_4-H_1930-1948.pdf " TARGET="TSC">4-HHistoryPreservation.com/eMedia/Alaska_4-H_1930-1948.pdf A territorial report in National 4-H News 60 years ago - January, 1953 - discusses the Mendenhall 4-H Club of Juneau. "Mrs. Joe Kendler of Juneau, Alaska, had read so much in dairy and farm papers about the fine work 4-H Club boys and girls were doing in the States and other places in the Territory that she decided it was high time Juneau youngsters got in on some of the fun. The trouble was – no one had time to be a 4-H leader. "If she wanted a club, she'd have to lead it herself. As partner with her husband in the dairy business, Mrs. Kendler had never been too busy to take part in civic affairs. Everyone knew the Kendlers, so with some help from the Extension agent, Mrs. Walker, the Mendenhall 4-H Club for boys was organized. "What they didn't know about club work far exceeded what they did know, but Mrs. Kendler's enthusiasm carried them through and this group has become one of the most active clubs in the Territory. "Ask Mrs. Kendler how she did it and she will say their best support came from good publicity – letting people know what they were doing, not just where and when they met. Thanks to good reporting, people of Juneau got quite intimately acquainted with the progress of Bill's calf, Johnny's chickens and Peter's goats. "Retired now from active farming, Mrs. Kendler says she has more time to enjoy the club. One of her boys was training his calf so he could dress it up like "Elsie" for the fair. Publicity, cooperation, plans – but above all, enthusiasm and understanding – are necessary factors for success. Kathleen Richard, Extension Editor." FRTEP – Extension's Support on American Indian ReservationsThe federal Bureau of Indian Affairs began to provide their own extension services on selected reservations sometime during the mid-1950s, however by the 1980s most of these programs no longer existed. In the late 1980's intertribal organizations at several locations joined together to petition Congress and federal agencies to create support for extension programs on Indian reservations. As a result, part of the 1991 Farm Bill (Food, Agriculture Conservation and Trade Act), authorized the Extension Indian Reservation Program (EIRP), now called the Federally-Recognized Tribes Extension Program (FRTEP), which is administered through the 1862 and 1890 Land Grant colleges and universities. FRTEP supports extension agents on American Indian reservations and tribal jurisdictions to address the unique needs and problems of American Indian tribal nations. Emphasis is placed on assisting American Indians in the development of profitable farming and ranching techniques, providing 4-H and youth development experiences for tribal youth, and providing education and outreach on tribally-identified priorities (e.g. family resource management and nutrition), using a culturally sensitive approach. 4-H and Extension Youth Programming on Indian Reservations During the Past 40 YearsReaching the youth of America's 500+ Indian tribes in recent years... and today, still does not seem to show clear patterns for either approach or programming. What successfully works in one area with one group of Native American youth may not work in another. But, again, this can probably be expected. It is not terribly different from 4-H's experiences in moving into inner urban areas. There was no singular program which worked everywhere. The neighborhoods were different. The needs were different. The families and the young people were different. Indian reservations present some of the same challenges. In an attempt to document the more recent history of the 1980s, 1990s and beyond, it seems appropriate to rely on those extension workers and volunteer leaders who lived it. The National 4-H History Preservation leadership team welcomes first hand stories about the more recent history of 4-H and Native Americans, as well as any links or references about this subject, which can be added to this important section of national 4-H history. Please contact us at Info@4-HHistoryPreservation.com Additional Information

Principal authors: Larry L. Krug |

|

|

| |

Compiled by National 4-H History Preservation Team. | |

|

| |

|

1902-2025 4-H All Rights Reserved | Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy The 4-H Name and Emblem are protected by 18 USC 707 |

|